Watch the performance

Suburbia Gallery, Granada.

May 2017

Everything in life is changing constantly; the urban environment and the countryside, both influenced by humans, are changing. Obviously the urban environment was built, while farming, forestry and roads have moulded the countryside. In this exhibition Pettena asks us to look with new eyes at urban and rural landscapes, non-judgmentally, paying close attention.

Hunting the Baron refers to a novel by Italo Calvino about the Baron, who decides to leave the city to live in the trees. He soon discovers that he enjoys living in the tree tops better than living on the ground, so he stays there, communicating with people below but refusing to come down. The Baron is detached from urban life, viewing it from a different perspective.

Pettena exhibited a video of the Baron leaping from branch to branch through the tree tops, followed by someone we perceive but cannot see, someone who is unable to catch up with the Baron.

>>> Watch the video <<<

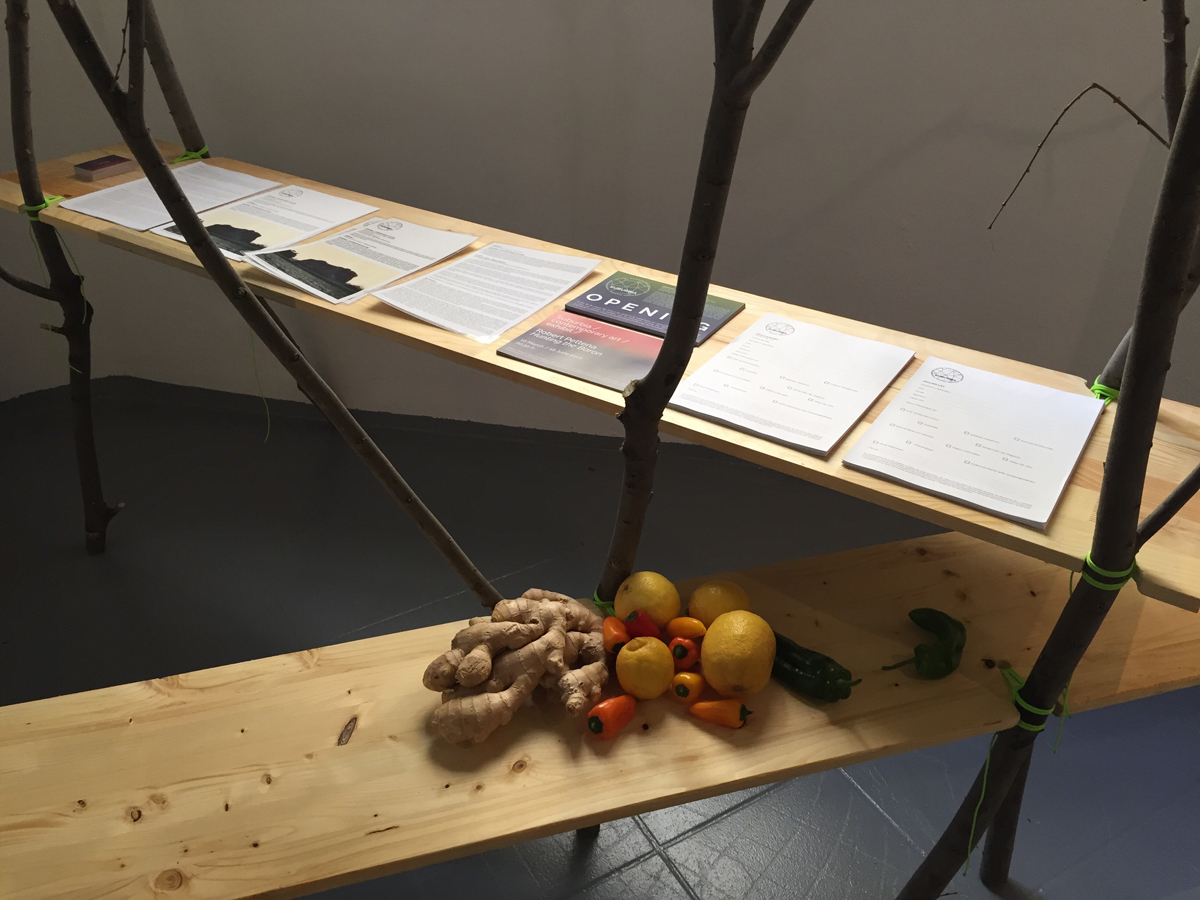

He built his Jungle junction bar from green saplings and planks, focussing on the way urban people are fascinated by the natural environment.

There were large format photos of scenes from nature, each containing a discordant note: in one case a super eight lm camera: to represent the recording, analysis, study and defence of the natural environment. In another photo there is a record player, to produce sound, just as Herzog does in his iconic film, Fitzcaraldo: the Conquest of the Useless, where the hero plays a recording of Caruso on his gramophone in the middle of the Amazonian jungle.

Pettena entrapped a young woman inside a wooden structure in a performance, again alluding to ways in which we are trapped within the urban environment, a metaphor for organic matter escaping from our control.

This installation was a reflection on the relationship between the urban and rural landscape and our perception of them.

Francesco Ozzola: Who are you and what do you do?

Robert Pettena: I spend all my time studying the dynamics of society and the powerful relationship it has with art and the art system, understanding the language of art and how this language changes and why it changes. Sometimes it changes faster than the cultural system in which it is embedded, and society struggles to follow.

FO: What's your background?

RP: I had a very alternative childhood, spent between England and Italy. Society was changing radically in the 1970s. Individual independence was becoming more important than the idea of the family unit and compromise between family members was no longer considered important. Left wing intellectuals were not keen on sacrificing their independence for the greater good of society. Utopian ideas were strong at that time. People wanted to change things drastically without considering whether it might have been better to make compromises for in the 1970s compromise was frowned upon.

I had the opportunity to experience the squatting movement in Brixton with all the subculture that this entailed. I was also taken to the Albion Fayres, small, alternative festivals where young people had the chance to develop their creative potential. In Italy too I experienced an alternative culture in the country side. Our parents encouraged us to express ourselves creatively right from an early age.

FO: How has your practice changed over time?

RP: My practice has always combined my desire to understand society with memories of my childhood. I can take a theme such as libertarian education and work on it in depth, but whatever the theme it will always be connected to my childhood experiences in some way. Libertarian education was something my parents believed in passionately.

When I started working on Nobel Explosion I was fascinated by Alfred Nobel's laboratory where he invented dynamite but where he also grew orchids. As a child I wanted to be an inventor - I loved inventing things - including explosives. Nobel was full of contradictions, a meta-example of corporate power.

Over time my art has changed outwardly from being apparently introverted to becoming apparently more extroverted, but how real is this change? Some of my later works, such as 'The Torture of Meditation ' at the Venice Biennial could be seen as something inward looking, though on the surface it may be critiquing society.

FO: What role does the artist have in society?

RP: I don't think the artist should have a role. The artist should be sensitive and aware of changes in society before they occur, like the canary in the coal mine. Art doesn't change society but the artist can draw people's attention to things that are occurring, things they might otherwise be unaware of. Whenever an artist takes a position he is manipulated by the powers above.

FO: What research do you do?

RP: One project in particular: Nobel Explosion, involved clear philological research to understand the dynamics of corporate power and the way in which it always has to present a positive image of itself. The Nobel corporation wanted the pubic to remember Nobel for his prize, not for the many types of explosives he invented and sold, causing death and destruction in so many countries. This made me think about the positive image of myself that I would like to create for posterity.

I did quite a lot of research for libertarian education, which shed light on my own upbringing.

But in the end my research is always connected with my childhood and the development of society.

FO: What makes you angry?

RP: I'm angry when I think about the way that the best art is always sponsored by the richest elements within an exploitative system. Art sustains the system, even when artists are critical of it, because the system finances them. As artists, whether we achieve fame or not, we give our life blood to the system. The inevitability of this short circuit makes me angry and this anger stimulates my creative juices.

FO: What's your dream project?

RP: I dream of living off my art, being able to develop art projects for people without interference from a system that uses the artist as a fragment to embellish itself, within a small, alternative society.

FO: Name something you love and why.

RP: When I travel I lose the idea of a destination or an objective and I begin to discover something in the transient relationships I make along the way, the food I taste, things I see. I love losing myself in the flow of the journey.

FO: Name something you don't love.

RP: I hate inhuman rules and restrictions that ignore the soul of the people. I detest authoritarian people who try to impose their ideas on others, manipulate people around them and engulf other people's ideas. Charismatic people tend to annoy me after a while. So I hate McDonalds!