Firenze.

2019

Un-mappable zones for a de-colonisation of space and mind.

Moving towards a new way to understand these spaces.

From the fifteenth to the nineteenth century the historical gardens of Florence and the surrounding countryside were theatrical spaces for the entertainment and delight of the guests of high society Florentine hosts. They were a fantasy land where nature and technology blended to create a symbolic journey that introduced the visitors to the host’s philosophic ideas. There were artificial grottoes, water tricks, statues and automatons. The gardens were continually transformed to provide an ever-changing spectacle of surprises, wonders, astonishment and beauty. They served as theatrical scenery for actors, musicians, acrobats and fire jugglers, who performed amid fireworks, fountains and water spectacles of every kind. In the Demidoff garden, for example, there was an entire underground system that moved the automatons and controlled the water spectacles above ground.

Mass tourism now has access to these historical gardens, which they treat as just another outing, visiting them briefly, without considering their historical context. Organised tours transport coach loads of tourists from one city to another, stopping briefly to visit the major sites, including some of the historic gardens, which have now become unchanging, static places. People wander about in the gardens without any idea of their spectacular past.

This project will seek to reactivate the parks through performances. Performers will dialogue with the garden spaces, bringing them to life in new ways and altering our perceptions of them. The performers will learn to live with all their senses within the environment, reading the place in a different way and reactivating the slumbering marvels of the historic gardens.

Cala Furia, Livorno.

2018

Accademia di Belle Arti di Palermo.

May 2016

The Workshop, half way between a relational art experiment and a video-photo urban intervention, was characterised by the direct involvement of the students in an experience in situ. It was designed to stimulate some kind of interdisciplinary discussion about the theory of perception, form and the language of contemporary art. The workshop, organised by the artist Robert Pettena, was based on the themes of the relationship between the perception and the enjoyment of place, based in the Palermo area. Certain points in the city are evocative of the past, both ancient and recent, causing forgotten stories and experiences to float up to the surface and act on the collective and individual psyche.

It was not a nostalgic homage, nor an archaeological investigation of abandoned architectural sites. It was more a becoming aware of place: immersing oneself in what is happening (reporting) rather than what happened (not reporting); but carrying out an analysis through the artist’s eye.

To bring the memory of a place to life is to bring the place to life: it takes on a different form.

See the project

2015

Curated by Marco Pierini, Galleria Civica di Modena, Palazzina dei Giardini.

December 2014 - March 2015

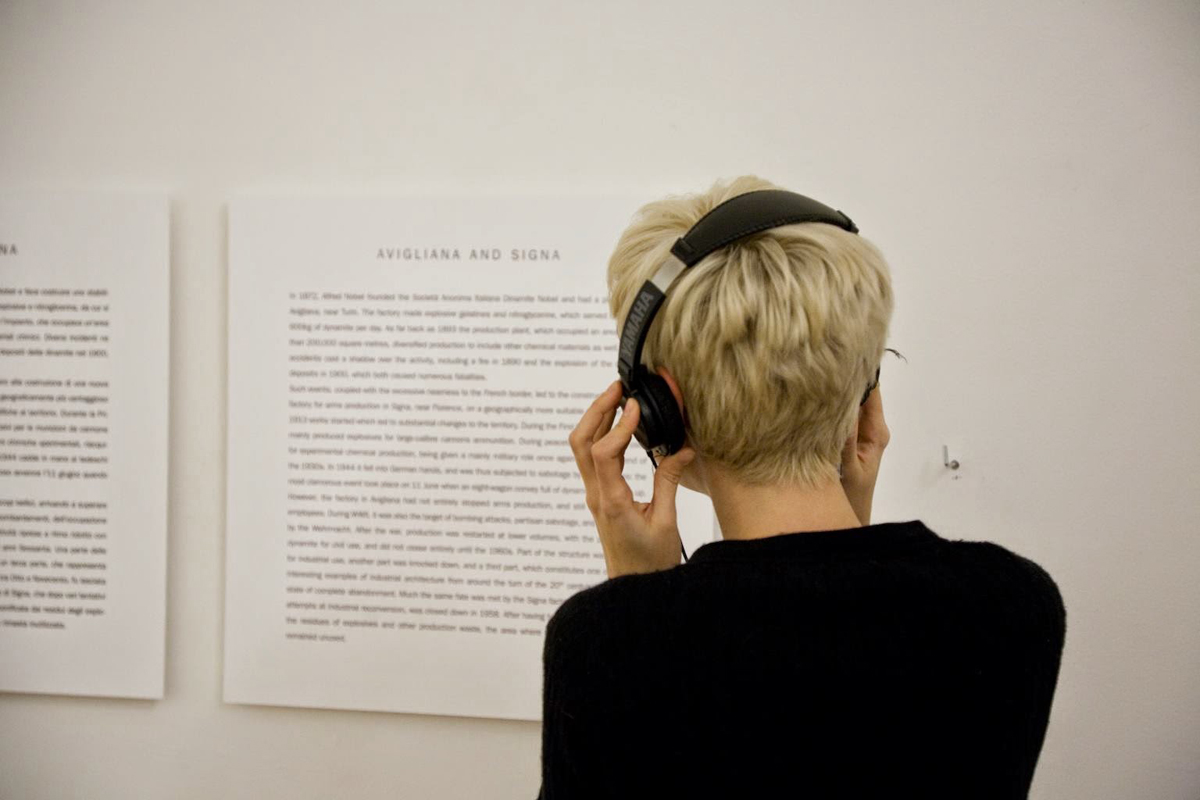

On Saturday 6 December at the Palazzina dei Giardini, in the Galleria Civica in Modena, the exhibition “Robert Pettena. Noble Explosion” opened. It was curated by Marco Pierini, co-produced by the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio of Modena with support from the Town Council of Spilamberto (province of Modena).

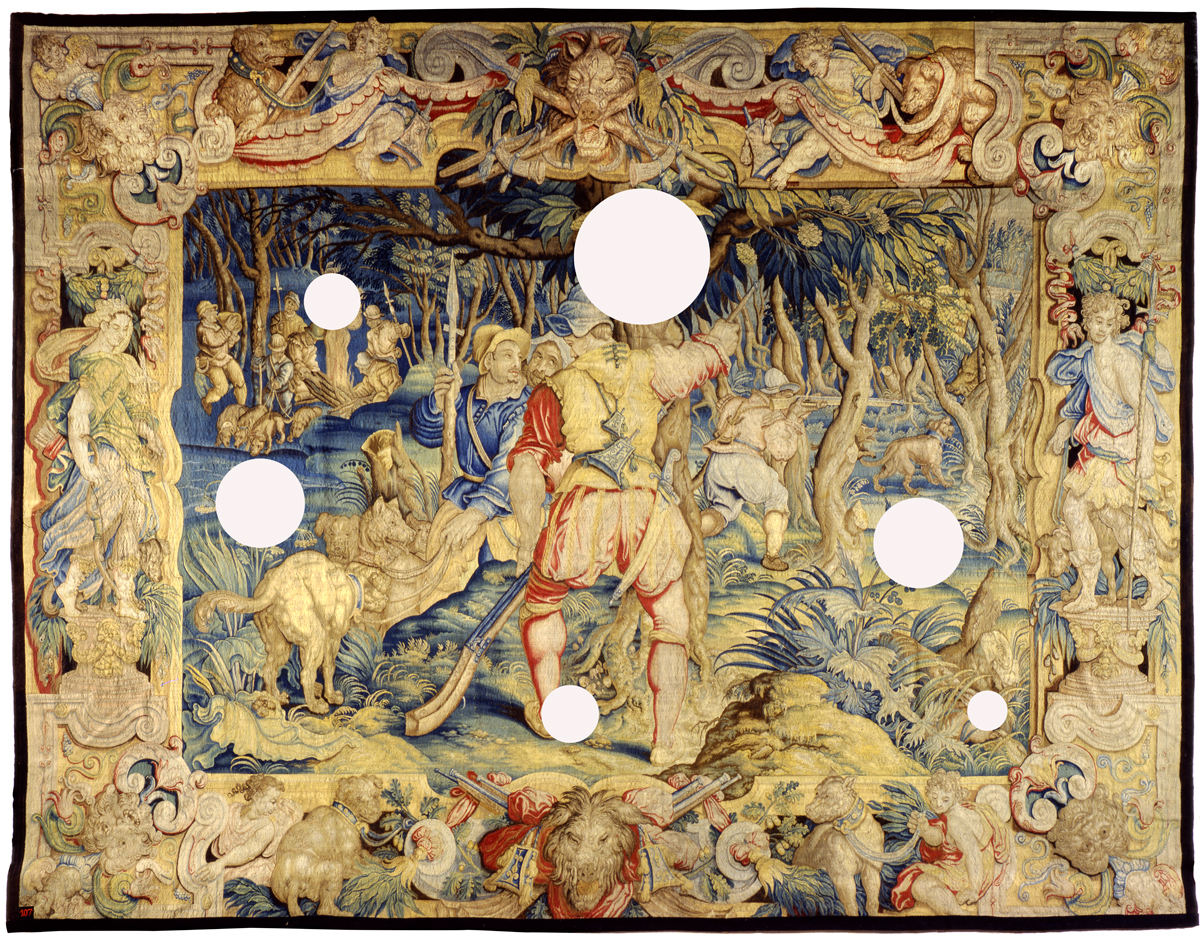

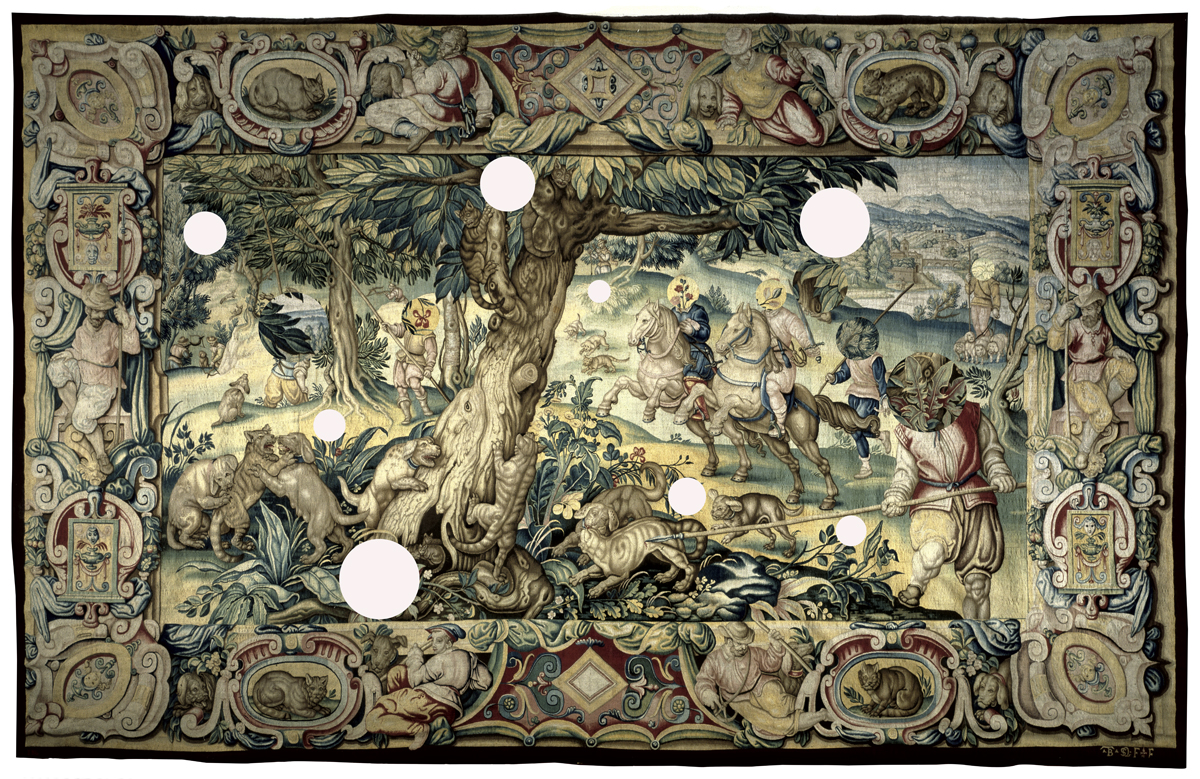

For the first time in Italy, the exhibition presented a wide-ranging photo survey by Robert Pettena of the SIPE-Nobel explosives factory sites in Italy.

Alfred Nobel, founder of the prize that to this day bears his name, was also and above all the inventor of dynamite. In the early 1870s, after encountering various difficulties in North-European countries, Nobel came to Italy to build his explosives production plants. Later, his company ‘Dynamite Nobel’ set up a successful joint venture with the Società Italiana Prodotti Esplodenti, thus leading to the foundation of SIPE Nobel SpA.

Dynamite, patented by Nobel in 1867, was used widely for mining, in quarries, in the construction and demolition sector. It also fuelled much of the development of the railway network, particularly in mountain areas, as it facilitated the drilling of tunnels. The growth in demand for explosives led to a boom in the industry. The Dynamite Nobel factory in Avigliana (province of Turin) first opened its doors in 1879. Between 1888 and 1900, SIPE Nobel produced around 120-130 tons of dynamite. In 1891 it began production in Forte dei Marmi of smokeless powders for the Navy, then in 1901 at Spilamberto, in the province of Modena and finally in 1903 at Cengio, on the border between Piedmont and Liguria, where TNT was produced for the Italian army. Throughout the First World War, the SIPE Nobel factories churned out dozens of tons of explosive powders and ammunition every day.

These elements provided the starting point for a fascinating study on the history and the paradoxes of one of the most complex figures of the late 19th century: an inventor, entrepreneur and philanthropist.

The show features a selection of around 50 photos and various other kinds of documentation (photos, drawings, archive materials) on the SIPE Nobel sites around Italy, with particular attention given to the Spilamberto site. Pettena’s photographic work highlights the compositional value of the industrial architecture around the turn of the 20th century, and the way they were integrated into the territory, often thanks to camouflaging with the surrounding vegetation to reduce the risk of airstrikes. “The artist’s eye,” writes Marco Pierini in the catalogue text, “observes the current condition of the factories almost clandestinely, and while he ponders the buildings’ state of abandonment, it is not with the aim of rediscovering an anachronistic taste for ruins, but to underline the exceptionality of places (often still waiting to be cleaned up) where time appears suspended and life – were it not for the vegetation reclaiming its space – is absent.”

A bilingual catalogue featuring critical texts by Angelo Bianco, Sandro Fussi, Francesco Galluzzi, Angela Paine, Marco Pierini, Marina Sorbello and Pier Luigi Tazzi was produced for the exhibition.

ANSWER MACHINE. INTER-VIS(I)TA ERMENEUTICA from Galleria civica di Modena.Angelo Bianco interviews Alfred Nobel. Voices by Fabrizio Orlandi and Claudio Ponzana.

Photographs by Robert Pettena. Editing and recording Matteo Orlandi.

Photographs by Robert Pettena. Editing and recording Matteo Orlandi.

A few question for Robert Pettena

ATP: Dynamite contains a potential energy that makes it a loaded symbol, at least as far as it relates to human beings. His invention needs someone to activate it, but it can destroy blindly. At the same time it can be used creatively and assist in the human progress: one only has to think of how dynamite is used in mining, construction and in the building of railways. What role does Nobel play in your project?

RP: Without doubt the nineteenth century can be considered the beginning of the modern era, with experimentation in the area of scientific and technological progress, leading to a multitude of inventions. Spiritism and science existed alongside each other, often exchanging roles; For example, Social Darwinism comes to mind or Cesare Lombroso’s Fisiognomica. The use of photography became a way to document scientific, as well as paranormal phenomena. It was during the second half of the nineteenth century that Alfred Nobel carried out his scientific experiments and laboratory tests, which resulted in the transformation of reactive substances. He patented 350 inventions, distancing himself from academia in order to work on practical uses for his inventions. Ascano Sobrero was the first chemist to synthesise nitroglycerine and Nobel was the first, after numerous failed experiments, to stabilise it, thus inventing dynamite and rapidly building up his economic empire. This was an invention that could cause mass destruction on the one hand, while on the other hand it could be used to accelerate the building of large public works.

Alfred Nobel was a tormented soul and a misanthrope with a profound belief in scientific progress and in human faculties. He believed in selling arms to both sides of a conflict in order to avoid either side having an unfair advantage (a cold war effect). Later he met Bertha Kinsky von Suttner, who was going to became his secretary, but left to marry her lover before she was due to start working for Nobel. She subsequently becoming a successful writer, thanks to her book Die Waffen Nieder (Lay down your arms.) She persuaded Nobel to espouse her pacifist cause and to finance many of her Peace Foundation’s initiatives. Her arguments went a long way toward convincing Nobel to leave money in his will for the Nobel peace prize.

Nobel’s love of his plants was as strong as his drive to patent new inventions while he grew more misanthropic and withdrew increasingly from bourgeois society. He had a winter garden in his house in Avenue Malakoff (now Avenue Raymond Poincarre) in Paris, where he cultivated his collection of orchids, right next door to his explosives laboratory. It was here that he invented ballistite which he went on to produce in Italy. This resulted in the French government accusing him of being a traitor to France for selling ballistite to their enemies, the Italians, so he moved to San Remo in Italy.

His contradictory relationship with explosives, which he manufactured for use as weapons as well as for large civil works, went on in parallel with his philanthropic support of pacifist organisations, particularly those set up by Bertha von Suttner.

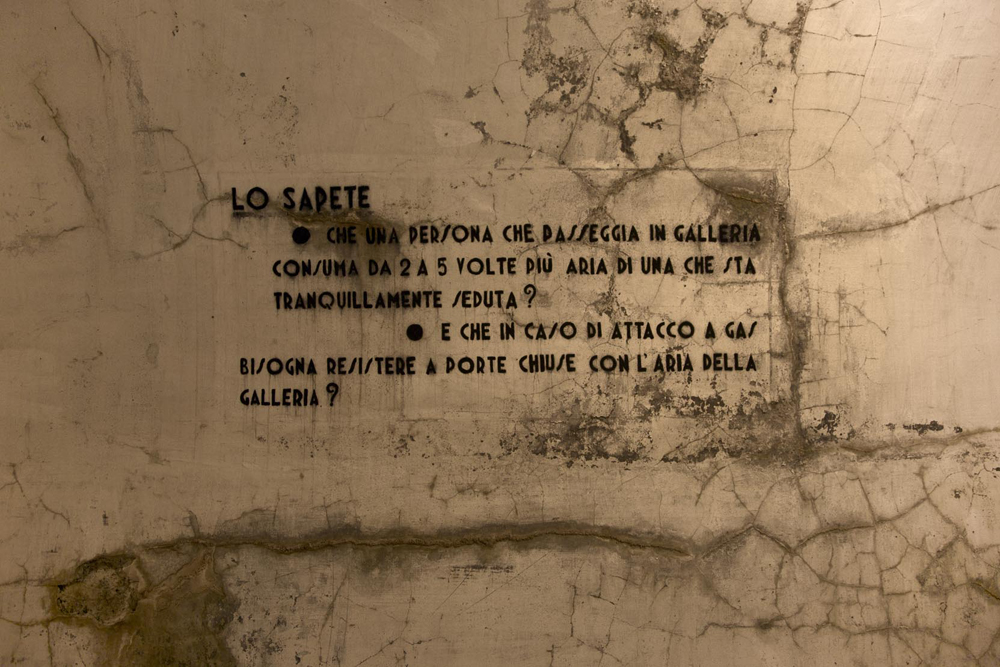

The discovery that at least seventeen factories built or acquired by Nobel in Italy for the production of explosives have remained covered in vegetation up to today, completely abandoned due to the high cost of decontamination, demonstrates once again the relationship between destruction and nature. It is as though everything had remained intact, according to the secret intentions of a man who wished to bind nature and destruction together through an immobile palingenisis, giving the buildings back to the parasitic plants, thus creating an architecture without form.

One breathes in an almost disquieting peace around these buildings, where it’s rare to come across an insect, let alone any kind of animal. They form enchanted cities. Every now and again the Nobel Peace prize floats across the back of my memory as I discover a new building that is both architecturally disjointed and covered in vegetation. There is an echo in the silence, a faint sensation of explosives industries rising to the surface and for a moment the Nobel Prize becomes a rumble below the surface.

ATP: Your photographs are not just about the history of Alfred Nobel and the production of dynamite. They are also a study of industrial architecture at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. What was the most interesting thing about these buildings?

RP: I made the casual discovery of the old explosives factory completely covered in brambles in the middle of Forte dei Marmi in 2010. That was when I began my photographic documentation of the SIPE Nobel industry. Travelling inland through the Tirreno I discovered this building that was completely covered in enormous brambles. The tourism industry had never been interested in buying the building and surrounding land because it was so polluted. It would have cost too much to decontaminate it. Another interesting site is the SIPE Nobel explosives factory at Spilamberto. The structure of the building goes all the way back to Napoleonic times. Although the SIPE Nobel company enlarged and altered the buildings at the beginning of the twentieth century they are an emblematic example of the development and demise of the productive cycle. They fell into disuse in 1990. The difficulty in re-utilising this industrial site, due to the pollution of the surrounding area, paradoxically preserves a unique architecturally historic place intact. My photographic work emphasises the structure of these examples of industrial architecture, which were often deliberately camouflaged with vegetation when they were built in order to hide them from arial bombardment.

Today the countryside is regulated and redesigned, through careful analysis of the territory, in order to preserve an eco-sustainable environment. Hiding places like the SIPE Nobel factories in this way would no longer be possible.

ATP: We often come across artists and their public who take an interest in a person or a building from the past. In your case you combine the two. I’m thinking of Tacita Dean and several other artists, each with their own aims, methods and results. It’s as if one wanted to write a poetic article, through images, and the artist were the invited guest, doubly special because he doesn’t fit into the five Ws but answers other questions using other means to tell his story: photography and video. Is there a particular narrative/documentary work that has had an impact on you as you were developing as an artist? And what do you think about this way of working?

RP: Every abandoned building has its own story and every story is mysterious. Ruined and abandoned buildings often rouse our curiosity and as we wander through the city and the countryside we are at the same time drawn to these places and slightly afraid of them. We immediately start imagining what could have happened there in the past and, thinking about their suitability as photographic material. As I travelled through the Tirreno, following in the steps of Pasolini in his Giulia, I was struck by that building completely covered in brambles in the heart of Forte dei Marmi. As soon as I found out that the building belonged to SIPE Nobel (the Italian Explosives Products Company) in partnership with Alfred Nobel, everything about it became more interesting and mysterious. My interest in the building led me to explore further, discovering other similar ones along the coast and in other Italian regions, all in the same condition. They were all abandoned, polluted and no one wanted to consider the expense of decontamination. Some of these places look like real industrial archeological sites and transmit a kind of heaviness that comes from the distant past. At the same time one feels drawn towards them by an uncontrollable desire to discover what they are all about, to understand their history, as though one were seeking Tarkovski's enigmatic dimension in “Stalker.”

As time passes nature increasingly takes these places over. We feel disorientated as we approach these SIPE Nobel buildings, by the lush vegetation that covers them, without ever fully understanding what it was like to work in them. We can only find out about the remaining buildings by looking inside them because we can’t really see the outside; they are so covered in vegetation. Yet we can deduce that they have an interior. These are back to front places, submerged views that can be documented and displayed. But inside there is an absence of appropriate references for a similar documentation.

ATP: I read that Nobel wrote a certain number of poems and plays and that at a certain point in his life he decided to dedicate himself to writing. I’d like to know what kind of poems and plays these were (if you came across any of them) and if these literary, and therefore artistic, aspirations of his were of any interest to you.

RP: It’s true that while he was living in Paris Alfred Nobel frequented various writers, including Victor Hugo. His love of classic literature is reflected in his work. He wrote a series of plays, novellas and poems of doubtful quality, considering that they’ve remained unpublished. I was interested in “the Enigma” that relates to the absurd destiny of man, who has, inevitably, to die although instinctively he feels immortal. This is a constant theme in his writing and goes some way towards explaining his attitude towards his own end, which he never accepted. Paradoxically Nobel, who refused to accept the enigmas of his own death, at the same time dedicated his life to the invention of ever more effective explosives for killing people. So rather than death being an enigma, it’s Alfred Nobel himself who is the enigma.

Interview by Clara Mazzoleni ATP

Spilamberto

Avigliana

Signa

Forte dei marmi

Orbetello

Montecatini

Campo Tizzoro

Cengio

Ferrania

San Remo

Stoccolma