Main Art Gallery, curated by Mike McGee, Cal State Fullerton Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana, California

2002

Windmills

“

Last summer I was the artist in residence in LA Cal Fullerton University working on my solo exhibition for the main art gallery. I was investigating the geopolitical power situation. Since I like to relate to where I am at any given moment, I wanted to relate to what I experienced in California where everything is big, open and vast. The windmills in the desert near Palm Springs are numerous and occupy a huge span of open space. I was very interested in that open space and it’s relationship to the human body. So I put a group of people in neon coloured shirts in front of the windmills, had them rotate their arms like the blades of the windmills, and video taped them.I was interested in how the windmill is emblematic of the relationship between people and nature. And I liked the idea that this particular emblem says something specific about California and how people relate to space and to the environment. For me, the idea of human beings imitating the interaction of nature with a manmade device is incredibly playful and interesting.

The number of times the windmill turns is directly controlled by the wind speed. The speed at which the blades rotate relates to the amount of energy produced. The windmill is an expression of the rigid control of time.

The high flying American lives according to a rigidly controlled time schedule. He yearns for freedom from the restrictions that surround him, freedom from the need to obey a multitude of rules in a rule-bound society. I was interested in the commercialisation of freedom, which is now sold in discreet sections of time: weekend breaks, etc. The students moving their arms like windmills in the wind farms combine the freedom aspect of the wide open space of the desert with the rigid discipline of the rhythm of the windmills.

”

Robert Pettena

“

Pentagon Play is about America. My point of departure was the “Jungle Gym” an American type of playground. The very name ‘Jungle Gym’ already expresses the concept that the playground is not a place for unplanned play, free expression and the development of creativity. The ‘Jungle Gym’ is designed by adults, as a place where children can learn to understand the rules, practice how to relate to and how to be accepted within the system.I saw sophisticated Jungle Gyms in rich areas like New Port, almost empty of children, with carefully constructed boats, bridges and even pentagon shaped towers - shaped like the ministry of defence - a subliminal message to the children. This shocked me. The real Pentagon is perhaps the most significant symbol of power in the world today. It symbolises a specific decision making process based on a military system of analysis and strategies. Children unavoidably react to a predetermined environment that reflects the culture and interests of the adults who created it.

I noticed that the parks in poor areas in Orange County were always full of children. Play-grounds in the poor areas were painted in ugly military green colours, built out of the wrong materials, with broken equipment, and dangerous. The children who play in these playgrounds fight for domination of the space, forming gangs with gang leaders.

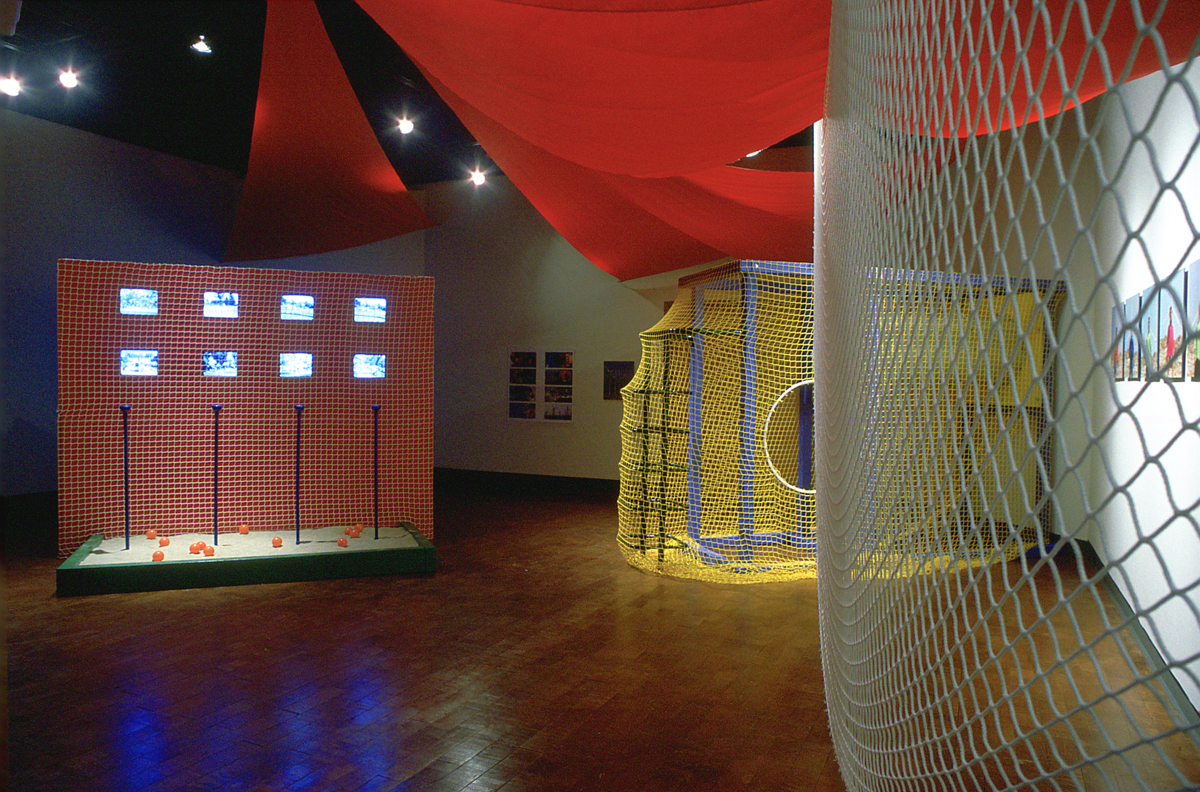

I created my playground installation in the gallery using the primary colours and plastic parts and components that can be found all over America. In a peculiar parallel to the spread of international corporate influence across the globe, these playgrounds which started in America have become international like Coca Cola, and MacDonald’s. I added stockbrokers to this environment because the stock market is also a game, a game involving a lot of money where stockbrokers react immediately to news or rumours in the same immediate and direct way that children play. The Stock Market is the ultimate playground.

”

Robert Pettena

Interview with Robert Pettena. Conducted August 29, 2002 at the Cal State Fullerton Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana, CA.

Mike McGee: Pentagon Play is the most complex artwork you’ve ever done.

Robert Pettena: Yes. In terms of technical complexities I’ve done more complex things. But in terms of having so many components this is the most complex and ambitious.

MM: This installation is a departure from your previous work in a number of ways. Your previous work is more corporal; it is usually about the body and the relationship between the inside and outside the body. Previously, your personal memories played a more substantial role. And you often used your own family as subjects in your videos.

RP: Yes, I like to relate to where I am at any moment. And being in California I wanted to relate to what I experienced here.

But, I began a lot of bits and pieces of this installation in Italy. I had begun to work on the windmill, for instance, before I came here. I learned about the windmill farms in California so I decided to visit the ones in Tuscany.

MM: Are the windmills in Tuscany contemporary?

RP: Yes, they’re very new; they just built them this year. They don’t actually supply power for the country; they’re only experimental at this point. There are only three windmills there. Many people object to them because they detract from the beauty of the countryside.

In Tuscany everything is small and neat and perfect: here it is completely different. Here everything is big and open and vast: big cars, big roads, big desert. The windmills in the desert near Palm Springs are so numerous and occupy such a huge span of open space. I am very interested in that open space and it’s relationship to the human body.

MM: So you put a bunch of people in neon coloured shirts in front of the windmill, had them rotate their arms like the blades of the windmills, and video taped them?

RP: Yes. I wanted to see how it looked. I already had these images in my head. So I knew that I could do this here. But afterwards, obviously, there are so many other ideas and relationships that start to pop up.

MM: Why are you interested in the windmills?

RP: In the beginning, I was interested in how the windmill is emblematic of the relationship between people and nature. And I liked the idea that this particular emblem says something specific about California and how you relate to space and to the environment here. For me, the idea of human beings imitating the interaction of nature on a manmade device is incredibly playful and interesting. Human beings don’t relate so neatly with nature. They relate more easily with the built environment, with the city. With the windmills you have these two often-opposing elements meet. It is a dialectic between the human and nature.

MM: What is the significance of the title Pentagon Play?

RP: Obviously, it’s about America. The pentagon shape is found in a lot of playgrounds today, but the reference to the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. is unavoidable. The Pentagon is where all the important decisions are made. It is the symbol of power; perhaps, the most significant power in the world today. The Pentagon symbolises a way of making decision: specifically, a military system of analysis and strategies.

MM: Then play is kind of the opposite of what happens at the Pentagon, another dialectic?

RP: Yes and no. During the Cold War, for instance, there was a lot of play between Russia and America. It was a big play going on. It was all about “I have a bigger ego. I’ve got a bigger submarine. I’ve got a bigger missile.” It was a game in many ways. And much of what goes on in the Pentagon today is a form of play.

MM: But there was and is specific structure to it. Whereas, children’s play in generally has less structured or involves less predefined structure.

RP: Yes. So a child starts playing with structures in his or her environment, but adults always create the environments children play in. So a child unavoidably is reacting to things that are predetermined and reflect the interests of adults and what’s going on in their culture.

It was interesting for me to discover that there are very few green, grassy areas in parks in Orange County. And it was also interesting to discover that the parks in poor areas are always full of children playing, while the parks in the more affluent areas were almost always empty.

It is also interesting and a bit bizarre that this woman Sandra Christensen put razorblades and other sharp objects in playground shortly after I began to work on this idea about playgrounds. I went to some of the playgrounds were she had done this. Even in these playgrounds in the poor neighbourhoods had lots of children playing about.

MM: The playground equipment in the installation with the primary colours and plastic parts and compartments can be found all over American. Is this kind of playground equipment in Italy too?

RP: Yes. In the past five to seven years this type of playgrounds are popping up all over the world. It is a peculiar parallel to the spread of international corporate influence across the globe.

MM: So these playgrounds have become international?

RP: Yes, like most of the global corporate influence they started here in American, and they are becoming common all over the world.

MM: So at the same time you find Coca Cola and Levi’s in every country around the world and Kentucky Fried Chicken and MacDonald’s in town and city these playgrounds are becoming the generic environment for children all over the world to play in.

RP: Exactly.

MM: And to this environment you’ve added stockbrokers?

RP: Yes. The stock market too is a game, a form of play.

MM: Albeit, a complex game involving a lot of money.

RP: Yes, involving a lot of money. And in the stock market people react immediately to news or rumours. It’s not like legislation, for instance, where the process of making laws and policy can take a long time. It is immediate and direct the way children play.

MM: There are stock markets in other countries, but America has the big stock market, and the majority of international corporations that have most impacted the world are represented there. So, it’s the big game.

RP: It’s the world’s biggest game: the ultimate playground.

MM: Tucked away in the back of the gallery is the hallway that ends with a projection of six people dressed in Victorian costume being served a meal they cannot eat because they are wearing plastic “Elizabethan” dog collars. How does this relate to the rest of the installation?

RP: The Victorian Age represents a seminal era in globalisation. It was the first time big companies influences truly became, not just international, but global. It is also the height of British world power, and it is the time when the transition from British to American world domination began.

The Victorian part of the installation is physically located in the back of the gallery, and it references the historical background that informs the rest of the installation. Without the Victorian era you wouldn’t have the same systems of play that are found in the front portion of the installation.

Food, of course, is a symbol and metaphor for wealth and power, but in the Victorian era much of the play that took place was based on manners and ways of behaving. Food had a lot to do with this play and way of behaving: not so much the consuming or eating of food, but the way food was dealt with. In the Victorian era there were very strict rule of conduct regarding the consumption of food.

MM: It was a game?

RP: Yes, and your facility to following the rules of the game communicated your membership in a specific sector of society. That’s why I had the actors wear the collars. The meal they are served has nothing to do with hunger. It has nothing to do with needing the food. It has to do with how you act according to the ethos and rules of the game.

I also like fact that these collars that are relatively new, they have been in use for maybe ten or fifteen years, yet they have this very old-referenced name—Elizabethan collars. And they’re for animals. The collars obscure your view of the actors faces so you only have scant visual clues as to what they’re thinking. You just have to guess. It’s like looking at an animal’s faces because you have enough information to develop some indications yet you can’t figure out exactly what they’re thinking. This kind of mystery about what’s really going on is, of course, very Victorian.

MM: The house behind the actors is Victorian, but it’s American Victorian.

RP: Yes. The presence of the American Victorian house in the background is a reminder of the relationship between Britain and America, and how Victorian influences were spread and interpreted throughout the world.

MM: Why did you want to cast in wax the heads of the actors for the Victorian video?

RP: Casting them in wax made their image completely loses any sense of being in this time. Casting is an old tradition, and it could have been done one hundred or two hundred years ago or now—there is no difference. And they also begin to relate to the tradition of casting faces of relatives, a tradition that goes all the way back to the Romans: this allusion is intensified by the way they are arranged on shelves in the hallway. The Russians used images like this to represent power. To put someone’s image in a situation like this denotes a sense that they belong to some specific history: perhaps a family or a powerful social order. Paintings and sculpture make histories and stories concrete.

MM: Is Pentagon Play an indictment of Western Culture?

RP: No. It’s not about judging people. It’s about observing things as they are and looking at the parts relative to the whole in ways that hopefully give the viewer opportunities to see things in a new ways. It is not my intention to moralise or make judgments about what people do. I don’t like the idea of judging people. I like the idea of giving sensibility to people. After all I’m part of this society. If I don’t like Western culture I should leave and go live somewhere else. In this installation I’m mostly interested in the mechanisms of play and the necessity of playing. Everyone needs to play—even world leaders. When Ronald Regan was President he would go off to his ranch in Santa Barbara and ride his horses. George Bush takes a lot of vacations. We all need to play.

Victorian Scene

“

The Victorian part of the installation was physically located in the back of the gallery, and it referenced the historical background that informed the rest of the installation. Without the Victorian era the systems of play in the front portion of the installation would never have come into existence.I was interested in the behaviour of Victorian aristocrats and the relationship between power and art. Works of art certificate a person’s social status and future generations recreate the origins of their family tree through the works of art that they have inherited.

I created a projection of six people dressed in Victorian costume being served a meal they could not eat because they were wearing plastic “Elizabethan” dog collars. The Victorian Age represents a seminal era in globalisation. It was the first time the influence of big companies truly became, not just international, but global. It was also the height of British world power, and it was the time when the transition from British to American world domination began.

Food, of course, is a symbol and metaphor for wealth and power, but in the Victorian era there were very strict rules of conduct regarding the consumption of food. It was a game and the ease with which someone followed the rules of the game communicated their membership of a specific sector of society. That’s why I had the actors wear the collars. The meal they were served had nothing to do with hunger but everything to do with behaving according to the ethos and rules of the game.

I also liked fact that these collars, which are relatively new, having been in use for maybe ten or fifteen years, have a name that refers to Elizabethan times, for they are called Elizabethan collars and they are for animals. The collars obscured the public’s view of the actors’ faces so that there were only scant visual clues as to what they were thinking. It was like looking at an animal’s face because there was enough information to get some idea yet it wasn’t possible to know exactly what they were thinking. This kind of mystery is, of course, very Victorian.

I placed the scene in front of an American Victorian house, as a reminder of the relationship between Britain and America, and how Victorian influences were spread and interpreted throughout the world.

I cast heads of the actors for the Victorian video in wax to give their image a timeless quality. These heads could have been created yesterday or a hundred years ago and there would have been no visible difference, for casting is an ancient tradition, much favoured by the Victorians.

”

Robert Pettena